Research Blends Psychology, Economics

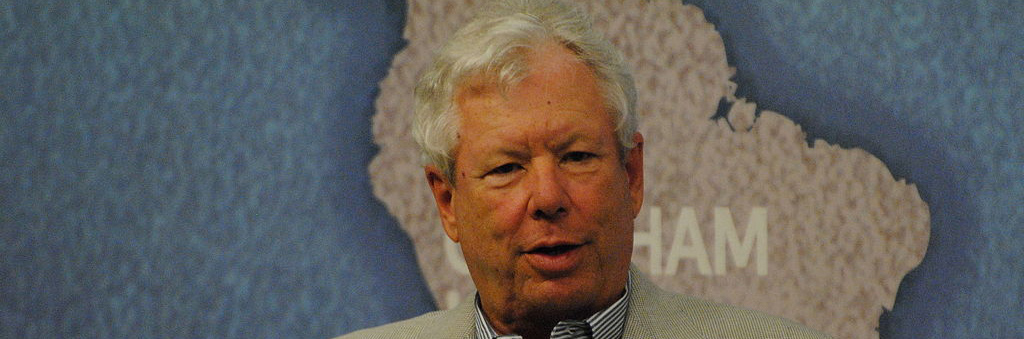

SMITH BRAIN TRUST – There was a time when Richard Thaler's research was considered highly controversial. Now, Thaler, one of the founding fathers of behavioral economics and author of the "nudge" theory, is the winner of the 2017 Nobel prize in economics.

The 72-year-old Thaler helped pioneer a field of research that blended psychology and economics. "It was something that just wasn't done before him," says Francesco D'Acunto, an assistant professor of finance at the University of Maryland's Smith School of Business.

Thaler, a professor at the University of Chicago, challenged a long-held precept in mainstream economics – the idea that people generally behave rationally when making financial decisions. He instead studied people's tendency to make decisions that work against their own interests, studying the places where economics and psychology intersect, and giving birth to the increasingly popular, though long controversial, field of behavioral economics.

D'Acunto became acquainted with Thaler about seven years ago, while working on his PhD at the University of California at Berkeley, where Thaler would often visit during winter term. "He was very engaged in giving advice to me and to others," D'Acunto says. "He was very generous with his time."

Much of D'Acunto's academic research relates to behavioral finance, the field that Thaler is credited with establishing. Among Thaler's most notable contributions is his "nudge" theory, which suggests that governments and companies can successfully encourage better retirement savings among workers simply by making regular, significant savings something that's done by default. In other words, he recommended doing away with intimidating enrollment paperwork, making retirement plans an opt-in choice, rather than an opt-out choice. He explained his findings in a best-selling book, "Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness."

Thaler's "Nudge" book was read by politicians around the world. Policymakers soon were changing laws to influence behaviors by using nudge logic. He worked with the British Conservative government under former Prime Minister David Cameron to change retirement savings policies for individuals, creating plans that assume that people want to set aside a portion of their income, unless they opted out. These policies are attractive to conservative administrations in that they have substantial effects on welfare and reduce the costs and size of government at the same time.

In the United States, meanwhile, the Obama administration, building on Thaler's work, created a behavioral economics unit to help draft economic and financial policy.

"At a time when savings for retirement are a very important issue both in the U.S. and abroad, with populations becoming older and labor force participation becoming lower over time," D'Acunto says, "these type of policies could really be able to make a difference in the lives of millions going forward."

British Prime Minister Theresa May more recently used Thaler's nudge concept to increase the number of people consenting to post-mortem organ donations. The change assumes that people want to donate organs upon death, unless they opt out.

Thaler is also known for his cameo appearance in the 2015 film, "The Big Short," in which he explained "the hot hand fallacy," one of the classic financial miscalculations that people make. It's the idea that a hot hand will continue to be hot, that rising valuations will continue to rise, or as he says in the film, "thinking that whatever is happening now is going to continue to happen in the future."

D'Acunto's latest research, a collaboration with Smith School finance professors Alberto Rossi and Nagpurnanand R. Prabhala, tests how algorithms and robo-advising might help overcome the most common behavioral biases that researchers like Thaler helped to document.

"Thanks to Dick Thaler's research, we know that investors tend to have mental accounts, that they don't tend to think about their full portfolios when making investment decisions," D'Acunto says.

In their work, D'Acunto and his co-authors found that the use of robo-advising algorithms could help mitigate those natural biases and promote better investment decisions. "It almost can wipe those biases away," D'Acunto says.

Thaler's work over the years has gone from highly controversial to increasingly accepted and increasingly influential in the mainstream of economic academia, D'Acunto says.

"What I would hope now," D'Acunto says, "is that people work hard in producing a unifying framework that incorporates some of Dick Thaler's insights into the neoclassical models of economic behavior."

GET SMITH BRAIN TRUST DELIVERED

TO YOUR INBOX EVERY WEEK

Media Contact

Greg Muraski

Media Relations Manager

301-405-5283

301-892-0973 Mobile

gmuraski@umd.edu

Get Smith Brain Trust Delivered To Your Inbox Every Week

Business moves fast in the 21st century. Stay one step ahead with bite-sized business insights from the Smith School's world-class faculty.